OnlineShow_BOOKLET_final.pdf

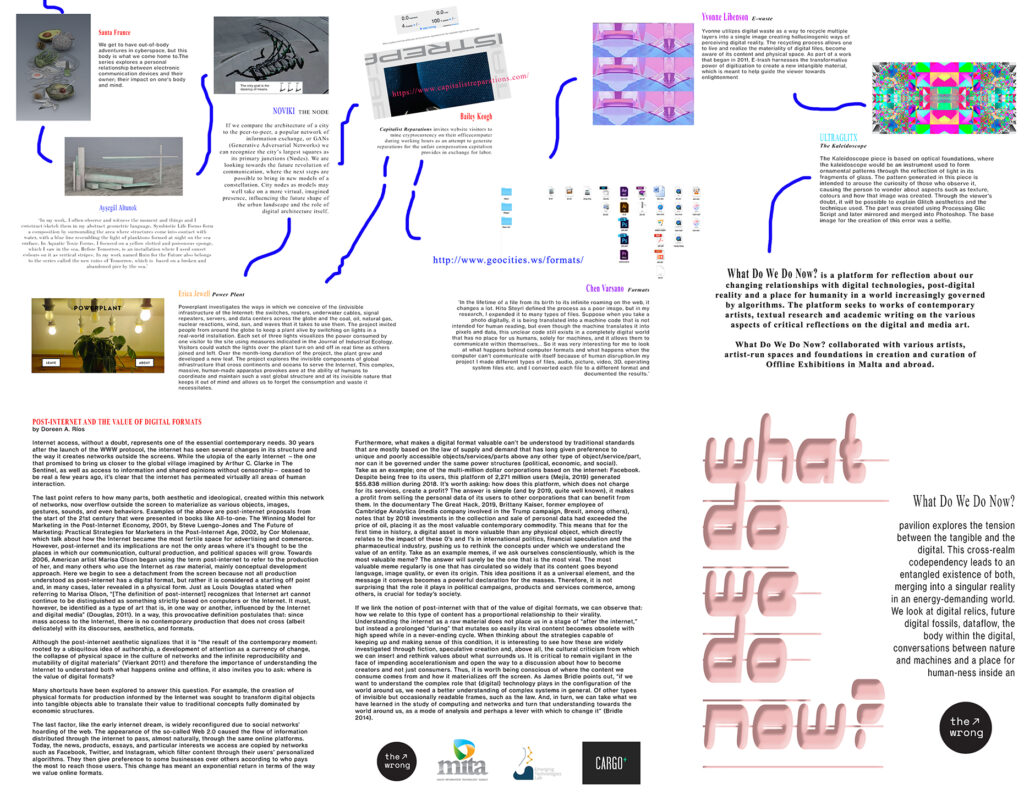

What Do We Do Now? pavilion explores the tension between the tangible and the digital. This cross-realm codependency leads to an entangled existence of both, merging into a singular reality in an energy-demanding world. We look at digital relics, future digital fossils, dataflow, the body within the digital, conversations between nature and machines and a place for human-ness inside an algorithmically customised reality.

Booklet text contribution

by Doreen Rios

POST-INTERNET AND THE VALUE OF DIGITAL FORMATS

Internet access, without a doubt, represents one of the essential contemporary needs. 30 years after the launch of the WWW protocol, the internet has seen several changes in its structure and the way it creates networks outside the screens. While the utopia of the early Internet —the one that promised to bring us closer to the global village imagined by Arthur C. Clarke in The Sentinel, as well as access to information and shared opinions without censorship— ceased to be real a few years ago, it’s clear that the internet has permeated virtually all areas of human interaction.

The last point refers to how many parts, both aesthetic and ideological, created within this network of networks, now overflow outside the screen to materialize as various objects, images, gestures, sounds, and even behaviors. Examples of the above are post-internet proposals from the start of the 21st century that were presented in books like All-to-one: The Winning Model for Marketing in the Post-Internet Economy, 2001, by Steve Luengo-Jones and The Future of Marketing: Practical Strategies for Marketers in the Post-Internet Age, 2002, by Cor Molenaar, which talk about how the Internet became the most fertile space for advertising and commerce. However, post-internet and its implications are not the only areas where it’s thought to be the places in which our communication, cultural production, and political spaces will grow. Towards 2006, American artist Marisa Olson began using the term post-internet to refer to the production of her, and many others who use the Internet as raw material, mainly conceptual development approach. Here we begin to see a detachment from the screen because not all production understood as post-internet has a digital format, but rather it is considered a starting off point and, in many cases, later revealed in a physical form. Just as Louis Douglas stated when referring to Marisa Olson, “[The definition of post-internet] recognizes that Internet art cannot continue to be distinguished as something strictly based on computers or the Internet. It must, however, be identified as a type of art that is, in one way or another, influenced by the Internet and digital media” (Douglas, 2011). In a way, this provocative definition postulates that: since mass access to the Internet, there is no contemporary production that does not cross (albeit delicately) with its discourses, aesthetics, and formats.

Although the post-internet aesthetic signalizes that it is “the result of the contemporary moment: rooted by a ubiquitous idea of authorship, a development of attention as a currency of change, the collapse of physical space in the culture of networks and the infinite reproducibility and mutability of digital materials” (Vierkant 2011) and therefore the importance of understanding the Internet to understand both what happens online and offline, it also invites you to ask: where is the value of digital formats?

Many shortcuts have been explored to answer this question. For example, the creation of physical formats for production informed by the Internet was sought to transform digital objects into tangible objects able to translate their value to traditional concepts fully dominated by economic structures.

The last factor, like the early internet dream, is widely reconfigured due to social networks’ hoarding of the web. The appearance of the so-called Web 2.0 caused the flow of information distributed through the internet to pass, almost naturally, through the same online platforms. Today, the news, products, essays, and particular interests we access are copied by networks such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, which filter content through their users’ personalized algorithms. They then give preference to some businesses over others according to who pays the most to reach those users. This change has meant an exponential return in terms of the way we value online formats.

Furthermore, what makes a digital format valuable can’t be understood by traditional standards that are mostly based on the law of supply and demand that has long given preference to unique and poorly accessible objects/services/parts above any other type of object/service/part, nor can it be governed under the same power structures (political, economic, and social). Take as an example; one of the multi-million dollar corporations based on the internet: Facebook. Despite being free to its users, this platform of 2,271 million users (Mejía, 2019) generated $55.838 million during 2018. It’s worth asking: how does this platform, which does not charge for its services, create a profit? The answer is simple (and by 2019, quite well known), it makes a profit from selling the personal data of its users to other corporations that can benefit from them. In the documentary The Great Hack, 2019, Brittany Kaiser, former employee of Cambridge Analytica (media company involved in the Trump campaign, Brexit, among others), notes that by 2018 investments in the collection and sale of personal data had exceeded the price of oil, placing it as the most valuable contemporary commodity. This means that for the first time in history, a digital asset is more valuable than any physical object, which directly relates to the impact of these 0’s and 1’s in international politics, financial speculation and the pharmaceutical industry, pushing us to rethink the concepts under which we understand the value of an entity. Take as an example memes, if we ask ourselves conscientiously, which is the most valuable meme? The answer will surely be the one that is the most viral. The most valuable meme regularly is one that has circulated so widely that its content goes beyond language, image quality, or even its origin. This idea positions it as a universal element, and the message it conveys becomes a powerful declaration for the masses. Therefore, it is not surprising that the role it plays in political campaigns, products and services commerce, among others, is crucial for today’s society.

If we link the notion of post-internet with that of the value of digital formats, we can observe that: how we relate to this type of content has a proportional relationship to their virality. Understanding the internet as a raw material does not place us in a stage of “after the internet,” but instead a prolonged “during” that mutates so easily its viral content becomes obsolete with high speed while in a never-ending cycle. When thinking about the strategies capable of keeping up and making sense of this condition, it is interesting to see how these are widely investigated through fiction, speculative creation and, above all, the cultural criticism from which we can insert and rethink values about what surrounds us. It is critical to remain vigilant in the face of impending accelerationism and open the way to a discussion about how to become creators and not just consumers. Thus, it is worth being conscious of where the content we consume comes from and how it materializes off the screen. As James Bridle points out, “if we want to understand the complex role that (digital) technology plays in the configuration of the world around us, we need a better understanding of complex systems in general. Of other types of invisible but occasionally readable frames, such as the law. And, in turn, we can take what we have learned in the study of computing and networks and turn that understanding towards the world around us, as a mode of analysis and perhaps a lever with which to change it” (Bridle 2014).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amer, K., 2019. The Great Hack (video). Netflix.

McHugh, G., 2011. Post Internet. Brescia.

Connor, M., 2013. What’s Postinternet Got to do with Net Art?, Rhizome.

Aleksandra Domanović and Oliver Laric in conversation with Caitlin Jones, page 114, MASS EFFECT, Art and the Internet in the Twenty First Century.

Wallace, I., 2014. What Is Post-Internet Art? Understanding the Revolutionary New Art Movement, Artspace.

Offline_show_booklet

design by Letta Shtohryn